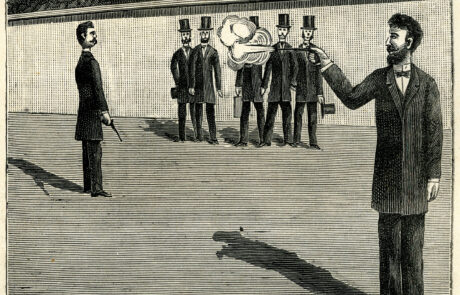

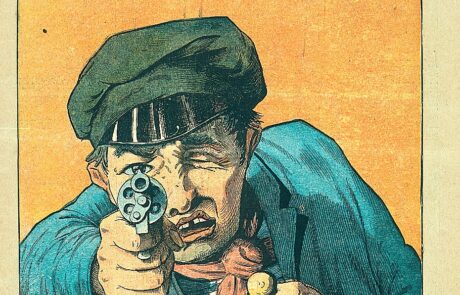

Milliam Sams, Two gentlemen duelling with pistols. Etching, 1823 (Wellcome Collection 568668i)

France

France stands out from other European countries due to its very late introduction of a gun licence system, which did not occur until 1939 and was prompted by war preparations, resulting in an accelerated redefinition of gun rights. Prior to this, the possession of non-military firearms was laxly regulated and the arms trade was relatively unrestricted. However, the carrying of firearms was governed by a complex and often misunderstood case law, which, for instance, prohibited the legal carrying of small firearms such as miniature revolvers. Gun control practices thus oscillated between the republican ideals inherited from the Revolution, during which firearms were seized from the nobility, growing perceptions of insecurity and criminality, and political concerns about the rise of an armed revolutionary citizenry in the wake of the Commune. The outbreak of the First World War introduced a system of authorisation for arms purchases, but – contrary to many other European countries – this did not lead to long-term disarmament. The French arms industry maintained its influence, as did the political rhetoric of maintaining the freedom to possess and use firearms righteously. Guns remained objects anchored in the needs of everyday life and were sometimes imbued with an additional symbolic layer as war memorabilia.

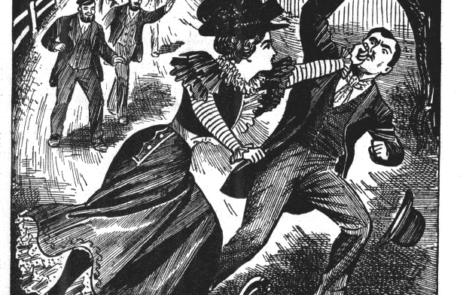

Therefore, the French case study provides an opportunity to examine the enduring normalisation of firearms in a country with numerous hunters, a multitude of shooting societies and a strong romanticisation of self-defence. Anxieties arising from urbanisation and industrialisation, an obsession with crime and criminals in popular culture and the gradual prosperity of a society embracing fashion and mass consumption all contributed to the view that pocket guns were useful tools for individual protection, until they were no longer welcome in homes and the risks associated with firearms were reassessed in terms of collective security.

Germany

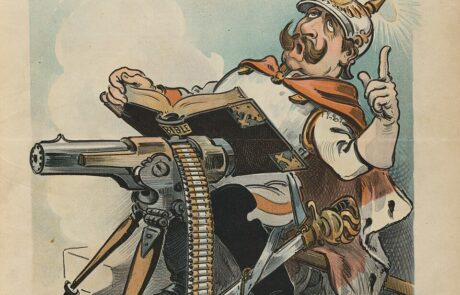

Germany’s path towards stricter gun regulation was heavily marked by external influence. Following World War I, the vanquished country – which most European states considered as the single most responsible for the outbreak of the war – was forced to undergo extensive demilitarisation and disarmament as stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles. It remains to be studied whether this was limited to military weapons or whether it also affected civilian firearms. Even before 1914, however, work had already begun on the first bill to regulate gun use and possession at a federal level, unifying the various gun statutes of selected municipalities and entire regions. However, parliamentary proceedings were interrupted when the war broke out. Following the Spartacist uprising and months before the signing of the Versailles Treaty, on January 13, 1919, the newly established republican government ordered the compulsory relinquishment of all weapons, both military and civilian. The unauthorised possession of firearms was strictly forbidden, as reinforced by a number of subsequent disarmament laws. Under pressure from the Allied powers and the socio-political turmoil of the early 1920s, the German government resumed work on a national firearms law, a process that took almost the entire decade and culminated in the passing of the 1928 Firearms and Ammunition Act. This was the first comprehensive bill regulating — and effectively limiting — access to guns nationwide. Later gun laws, including the 1938 Nazi and 1972 West German versions, were modelled on this bill.

Significantly, Germany was one of the first countries in Europe to introduce licences for carrying firearms in public. Before 1928, however, these could only be issued for one’s own police district and neighbouring districts or region at most. Furthermore, the country had a strong tradition of shooting clubs and hunting; the latter was notable for its exclusivity, which was a result of the influence of the aristocracy and the grande bourgeoisie. Shooting associations and hunters were successful in securing exceptions and more lenient treatment with regard to gun control and disarmament measures, including after both world wars and in the allied-occupied region of Rhineland, which attests to their privileged position in the German gun culture of that time.

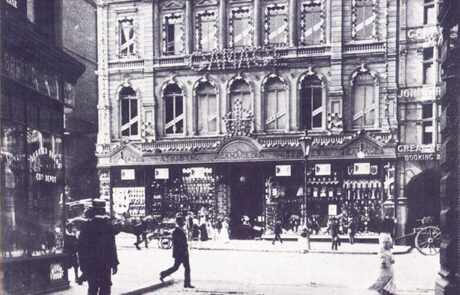

Great Britain

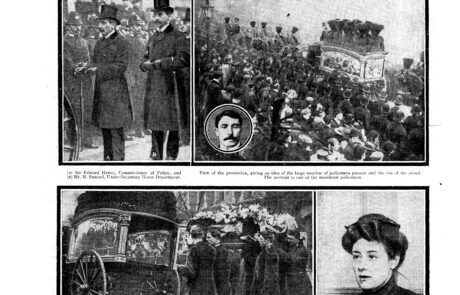

Gun regulation in the United Kingdom evolved through a slow process, largely shaped by debates over crime, public safety, and the proper limits of state authority. In the late nineteenth century, although concerns about armed robbery and political violence were growing, repeated parliamentary attempts to restrict firearms ownership failed, often considered as unnecessary or overly paternalistic. The Pistols Act of 1903 introduced basic restrictions – such as a minimum purchase age and licensing requirements – but was widely regarded as weak and ineffective. A turning point came in the aftermath of the First World War, when the government, alarmed by the return of demobilized soldiers, rising labour unrest, and the perceived threat of a Bolshevik revolution, sought to impose stricter controls. The Firearms Act of 1920 required police-issued certificates for the possession and purchase of firearms, and notably, it rejected personal protection as a legitimate reason for gun ownership. This legislation marked the beginning of a broader shift in British firearms policy, in which the state assumed increasing responsibility for civilian safety.

During the interwar period, new laws targeted imitation firearms, airguns, and young users while extending the power of the police to determine who could legally own a weapon. In this regard, the Firearms Acts of 1934, 1936, and 1937 progressively raised the age limits for ownership, introduced stricter licensing rules, and reinforced the idea that only sport shooting or organized clubs had justified access to guns. These laws reflected a broader political consensus that firearms were not appropriate tools for civilian defence but potential threats to social order. Ultimately, by the mid-20th century, Britain had created the framework for a heavily regulated and largely unarmed civilian society, a model reinforced after World War II with stricter enforcement, public amnesties, and a clear delegation of protection responsibilities to the state and police forces.

Italy

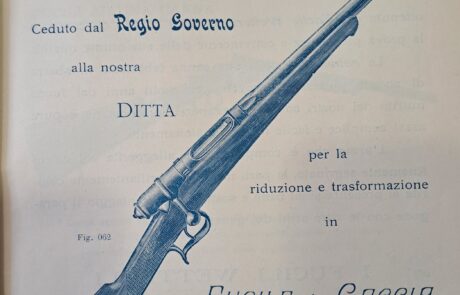

While nineteenth-century Europe largely lacked systematic restrictions on the circulation of civilian weapons, the Italian Kingdom tightly regulated the carrying of firearms since its foundation, establishing a licencing system rooted in the legislation of pre-unification states. In the challenging post-unification context, which was marked by institutional fragility, high rates of violent crime and a severe public order crisis in southern Italy, the right to carry a gun was not considered universal, but rather a conditional privilege. This was achieved through the selective issuance of gun licences to trustworthy individuals, while systematically excluding the lower classes and those perceived as politically or socially unreliable.

Nevertheless, this system proved capable of adapting to the evolving scenario shaped by the ongoing technological evolution of firearms. Between 1887 and 1889, in an effort to limit the growing circulation of fast-firing, concealable revolvers, the Italian government introduced a substantial distinction between carrying rifles for hunting and recreational purposes, and carrying pistols for personal defence, which was only allowed upon demonstration of legitimate reasons.

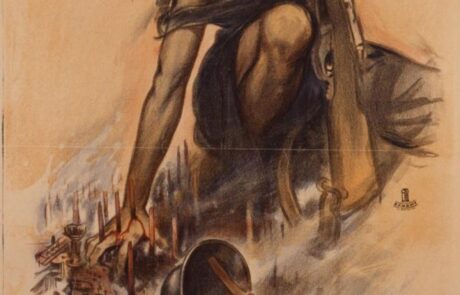

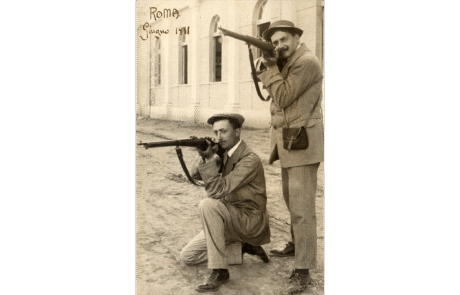

This set a groundbreaking legal framework that would resonate well into the modern era. Despite such regulatory constraints, Italian governments consistently promoted shooting activity (tiro a segno), which was widespread across the country, while the fascist dictatorship fuelled a militaristic rhetoric in which gun practices were promoted as a formative tool in shaping the character and discipline of young male citizens. At the same time, hunting remained, up to the early twentieth century, the most widespread recreational activity among the Italian elites and middle classes.

Given these peculiarities, the Italian case study represents a compelling point of comparison with other European countries. It prompts reflection about the implementation of gun control measures and the gradual shaping of a gun culture within a broader context of political transition from a liberal state to a fascist dictatorship.

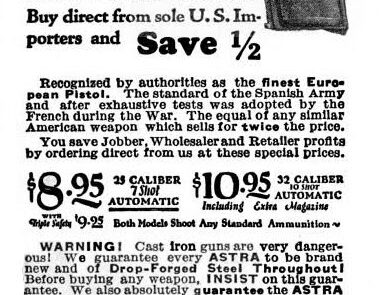

Spain

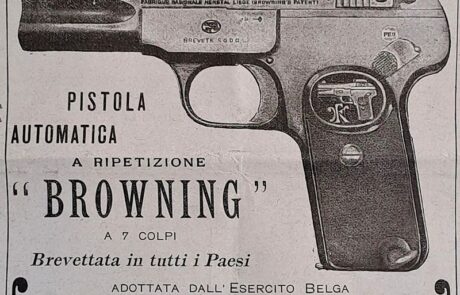

Despite often being viewed as a peripheral actor in European affairs, Spain occupied a central position in the global arms industry during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With manufacturing concentrated in the Basque Country, the country became one of the world’s leading producers of small arms. By 1905, the district of Eibar ranked second in Europe – surpassing Birmingham and Saint-Étienne – with more than 450,000 firearms produced, nearly 80% of which were destined for export. This remarkable industrial and commercial dynamism positioned Spain as a key global exporter during the interwar period, bolstered by a competitive domestic sector and a permissive legal framework. At the same time, however, Spain struggled to manage the internal circulation of firearms, exposing the gap between regulatory ambition and practical enforcement.

This set a groundbreaking legal framework that would resonate well into the modern era. Despite such regulatory constraints, Italian governments consistently promoted shooting activity (tiro a segno), which was widespread across the country, while the fascist dictatorship fuelled a militaristic rhetoric in which gun practices were promoted as a formative tool in shaping the character and discipline of young male citizens. At the same time, hunting remained, up to the early twentieth century, the most widespread recreational activity among the Italian elites and middle classes.

Given these peculiarities, the Italian case study represents a compelling point of comparison with other European countries. It prompts reflection about the implementation of gun control measures and the gradual shaping of a gun culture within a broader context of political transition from a liberal state to a fascist dictatorship.

This took place against a backdrop of sustained social and political violence. Between 1917 and 1923 alone, more than a thousand individuals were involved in armed clashes that left over 200 dead in the city of Barcelona, this being just one example of Spain’s emergence as one of the most violent hotspots in post-World War I Europe. Firearms circulated widely across society: among revolutionary workers’ organisations, right-wing militias, employers’ associations, and even ordinary citizens – driven both by concerns for self-defence and a strong tradition of hunting and civilian marksmanship. This circulation was propelled not only by social conflict, but also by the broad availability of domestically manufactured firearms and a legal framework that was ultimately ineffective. In fact, although a licencing system was established in 1876, the illegal possession of firearms was not criminalised until 1923, highlighting the limits of a legal model that, rather than controlling, allowed the state to manage the presence of weapons strategically.

The Spanish case offers a striking example of the paradoxes inherent in gun control policies during periods of political crisis. Despite the introduction of increasingly restrictive measures from the 1920s onwards, levels of armed violence remained high. Legal frameworks coexisted with institutional practices of tolerance or even encouragement of armament in specific sectors, particularly when aligned with efforts to maintain public order. Rather than merely reducing violence, these measures were often employed to manage it strategically, disarming perceived dissident groups while granting access to social sectors deemed loyal. Spain’s experience thus highlights the complex relationship between regulation and armed citizenship, revealing how gun control can function not only as a mechanism of security, but also as an instrument of governance in times of contested legitimacy and social unrest.

Sweden

Before 1918, Swedish citizens were free to buy and own guns without obtaining a licence, and the “right to bear arms” was at times heralded as a constituent part of Swedish political tradition. As the First World War drew to a close, however, increased fears of what guns might do in the hands of the wrong people caused the government to issue restrictions on sales, and subsequent increases in control culminated with the passing of a licence law in 1934. This transformation from one of Europe’s least restrictive control regimes to one of its strictest raises pressing questions about the relationship between gun control and social, cultural, and political change regarding the concepts of freedom and security, which this project will investigate thoroughly.

At the same time, tighter gun control did not by default equal diminishing gun cultures or practices, which is not least demonstrated by the fact that Sweden still has one of the highest gun ownership rates in Europe per capita. Rather, the EU-GUNS project will analyse the period between 1870 and 1945 as a period of transition and transformation for various expressions of the Swedish gun culture, which were not necessarily weakened by tighter gun control. Particular attention will be paid to cultural constructions of lawful civilian gun practice and its relation to the understanding of guns as material objects in society.

Not least, organised leisure activities became prominent features of the Swedish gun culture during the period, as hunting and sports shooting both constituted widespread social practices and underpinned the imagined Swedish identity. Hunting, especially of elks, became a symbol of popular Swedishness, while shooting sports during the early 20th century became entangled in a wider sports movement eager to display Sweden’s character and modernity to the rest of the world. Therefore, by analysing such activities, this project will also promote an appreciation of the importance of leisure and play for the potential of guns to frame and construct cultural practices and understandings.

![5. [Recueil_Oeuvre_de_Bernard_Beaudier_[…]Beaudier_Bernard_btv1b104627899_1(1)](https://euguns.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/5.-Recueil_Oeuvre_de_Bernard_Beaudier_.Beaudier_Bernard_btv1b104627899_11-460x295.jpeg)

![6. Fonds_Georges_Lafaye_(1915-1989)_III_[…]Lafaye_Georges_btv1b54100121c_1(1)](https://euguns.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/6.-Fonds_Georges_Lafaye_1915-1989_III_.Lafaye_Georges_btv1b54100121c_11-460x295.jpeg)